Back in 2010 it was found that baby rats are born knowing which direction is which. That is to say, their head direction cells (HD cells) were fully mature and ready to use by the time they came to leave the nest. The question immediately arises then, which is that if humans are also born with a sense of direction, as rats are, why are some people so good at getting lost?

Researchers have identified two other cells in the brain—place cells and grid cells—and it is the way in which these interact which most likely explains why some people are better able to navigate a route between two points.

Place cells are thought to help us form a mental map. They were identified by Professor John O'Keefe, who made his breakthrough discovery in 1971, when he observed that certain nerve cells in rat brains were always activated when the rats were in one part of the room, others were activated when they moved to a different part of the room, and so on. This led him to the conclusion that these place cells, located in the hippocampus part of the brain, constitute a map of the space that is stored in the rats' memory.

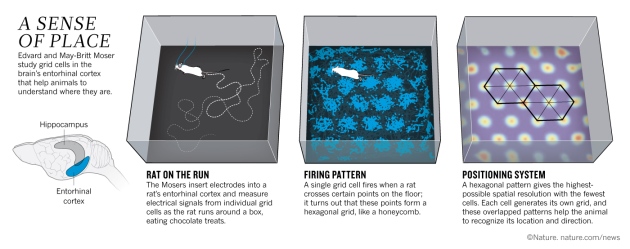

Grid cells enable us to keep track of where we are, even in an unfamiliar place. They were identified by Professors Edvard and May-Britt Moser, and are located in the entorhinal cortex (the main interface between the hippocampus and neocortex). "The 'grid map' is like an empty map," May-Britt explains. "So it's like longtitudes and latitudes without the map. So you have a coordinate system. And then you have the communication with the hippocampus, where you have the memory. And the memory for the landmarks, for the environment, for everything, is put on top of this coordinate system."

"Without grid cells, it is likely that humans would frequently get lost or have to navigate based only on landmarks," Dr Joshua Jacobs has said. "Grid cells are thus critical for maintaining a sense of location in an environment."

|

| Image from Nature magazine |

Dr Michael Kahana has added: "The present finding of grid cells in the human brain, together with the earlier discovery of human hippocampal 'place cells', which fire at single locations, provide compelling evidence for a common mapping and navigational system preserved across humans and lower animals."

This simple arrangement is complicated, however, by the fact that in laboratory conditions—which are about as far removed from normal day-to-day living as it is possible to get—gender differences become more noticeable. In some tests men do better than women, in other tests not.

"Thirty-five individuals were blindfolded and driven in a bus around a circuitous route for almost 20km in an Australian country town. At four points they were asked, whilst still blindfolded and in the bus, to indicate the direction of the point of origin of the journey. When the mean vector and the homeward component were calculated from the estimates, participants proved to be able to sense direction reasonably successfully. Females tended to have a better sense of direction than males" (source).

The Daily Mail writes that women "generally have a poor sense of direction" (source). The Royal Institute of Navigation (no less) goes even further: "It is a known stereotype that [...] women have no sense of direction" (source). Clearly this is not the case. What seems more likely is that women use the intellectual part of their brain more than men do when faced with certain navigational tests. For example:

"Male and female subjects were given the task of navigating through an unknown virtual 3D environment and the resulting brain activity was captured with fMRI scanning. Whilst there was a lot of overlap in the activated parts of the brain, a differential analysis showed a significant variation in brain activity between men and women. Women showed greater activity in the left and right pre-frontal regions, while men showed increased levels of activity in the hippocampus" (source) [pdf].

A study carried out by Professor Eleanor Maguire and Dr Hugo Spiers looked at how taxi drivers use the hippocampus and other brain areas as they navigate. This they did by getting the taxi drivers to drive a route in London using a virtual reality simulation, and recording the brain activity with an fMRI brain scanner.

The researchers found that the hippocampus is most active when the drivers first think about their route and plan ahead. When they encountered road blocks or other obstacles during the simulation, other areas of the brain were involved. The researchers also found that a part of the brain called the medial prefrontal cortex increased its activity the closer the taxi drivers came to their destination.

The hippocampus is the older (in evolutionary terms) part of our unconscious mind. It is also the part of the brain where place cells are found. It is thought that place cells help us to form a cognitive map, which serves an individual to help him or her acquire, store and recall information about the relative locations of his or her spatial environment. Thus:

"In tests of ability to navigate virtual 3D environments, there wasn’t a significant difference between men and women in success levels as long as the landmarks were left in place. When these were removed, men showed an ability to keep their bearings and had a significantly higher degree of success" (source).

When the landmarks were removed, the 'map' of the virtual world which the females had constructed in their heads was abruptly rendered incomplete. The males, who usually have difficulty finding a pair of socks in the airing cupboard, wouldn't have paid much attention to the landmarks in the first instance, and so were not unduly affected by their sudden disappearance.

“Everybody knows that men and women have some biological differences—different sizes of brains and different hormones," psychologist Tom Stafford has said. "We also know that we treat men and women differently from the moment they’re born. Brains respond to the demands we make of them, and men and women have different demands placed on them.”

Even so, it may be that men and women use different parts of their brain to navigate a route as a consequence of our hunter-gatherer heritage (source). Because women were more likely than men to forage for food, they were more liable to find themselves lost within a relatively short distance of the village. There was, therefore, every advantage to them in being able to memorise routes, particularly when—in situations like this—it is so easy to become disorientated. Likewise, because men were more likely than women to venture some considerable distance from the village on hunting trips, there was every benefit to them in being able to find a way home by "following their nose".

In summary, I am certainly not suggesting that men do not also use landmarks to keep them on track, and nor am I suggesting that women do not also rely on a sense of direction to help them navigate a route. I do however think that there are different emphases, and that these are more likely to manifest themselves in extreme situations, such as are found in laboratory conditions.

|

| Navigation device from the Marshall Islands (Polynesia) showing directions of winds, waves and islands. Photo credit: National Geogrphic |

Before closing, I would like briefly to discuss a related matter. According to Wikipedia, navigating a route between two points basically involves four stages:

i. Orientation (which, as discussed above, is a function of the mind, and is the ability to locate oneself with reference to place).

ii. Route Decision (which is the selection of a course of direction [my emphasis] to the destination).

iii. Route Monitoring * (which is the checking process to make sure that the selected route is heading towards to the destination).

iv. Destination Recognition (which is when the destination is recognised).

* It is during this stage that people are most likely to become disorientated. Route confirmation markers (like Hansel and Gretel's bread crumbs) are therefore essential, particular on Quietway routes (see also here).

|

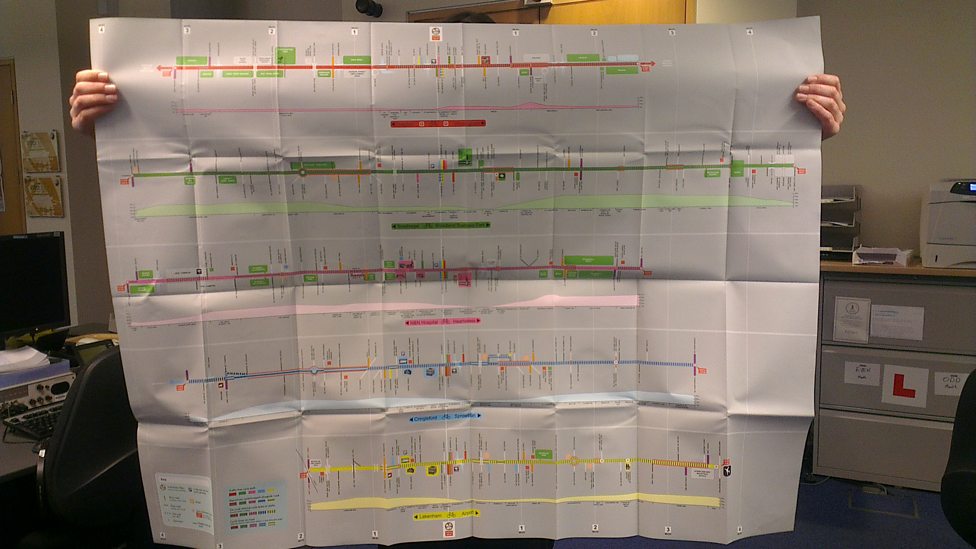

| Norwich Cycle Map Image from BBC Radio Norfolk |

P.S. I was telling a friend about this blog, and when I got to the bit about the socks and the airing cupboard, she said that it reminded her of the time her son had come to her asking for a clean shirt. "It's on the end of your bed," she told him. He came back a minute later and said it wasn't there. So they went into his bedroom together, and she pointed it out to him. "Oh," he said, "the other end."