Whilst this idea has a great deal of validity, particularly in large towns and cities, my strongly-held view is that this approach should never be pursued to the detriment of the acknowledged benefits of cycling. People cycle for all sorts of reasons: because it's cheap, yes of course, and because by so doing their mental, physical and spiritual well-being is improved; but significantly, I believe, the main reason people cycle in the built-up area is because it is very often quicker and more convenient than the alternative forms of transport. A strategy which fails to take regard of this is extremely likely to fail, in my opinion. Indeed, as Jim from Drawing Rings has noted: "If people have to go around the houses to feel safe on a bike, many of them will just take the car instead."

|

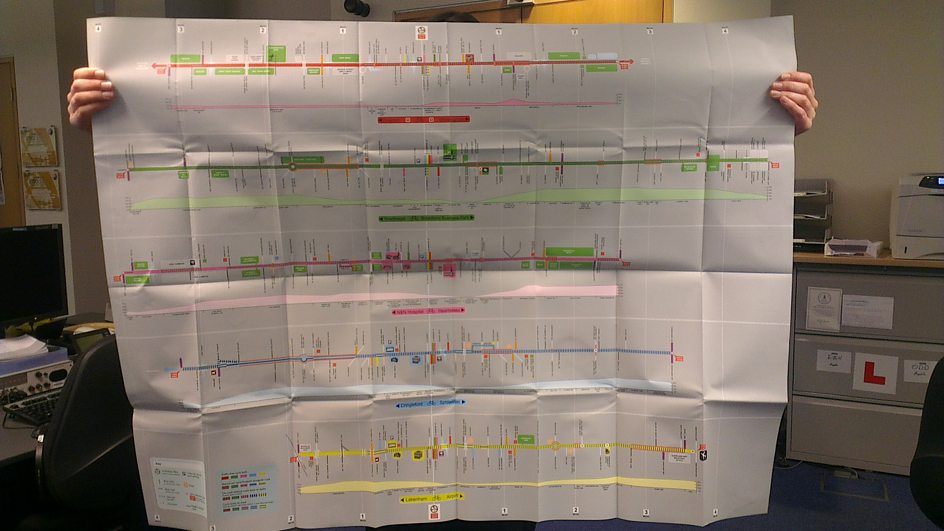

| A snapshot of the Connect London network. To read a critique of this project, please refer to this blog from Mark Treasure. |

Jim continues: "If we can make the quick and direct routes safe and comfortable to cycle, then many people will find that cycling suddenly makes sense for them. This is what happens in the Netherlands, where people are not expected either to brave unpleasant conditions on main roads, or to work out a convoluted but quiet route on back roads. By making cycling safer, they have made it quicker too, and that's the key."

I wholeheartedly agree. The question is, of course, how to bring about this happy state? One option would be to heed Carlton Reid's advice, whose "stance," he says, "is one of pragmatism, and lots of little actions."

This is my stance, as well. The difference is that I would just try to do as many little actions as possible as quickly as possible, and I would do them to a plan (top-down). Carlton, however, seems to see things in a different way, thus:

How about pushing for lots of smaller goals? This is a stealth tactic that can work. For instance, in your locality, campaign for a certain road to be closed to traffic with bollards. Just one road. Not much to ask for. But then, after this success, pick another road and work hard on getting that closed to cars, too. Do this lots of times and, eventually, there will be a permeable network for cyclists.Eventually? Well, okay, but as Frank Lloyd Wright has noted: "Eventually I think Chicago will be the most beautiful great city left in the world."

Sure, sure, you keep hammering away, and eventually the nail will sink. But if the only tool available to you is a hammer, then pretty soon you will start to see every problem as a nail.

A bruised thumb

In a recent blog entitled Resistance to change, Mark Treasure makes the strikingly good point that where there genuinely isn’t enough road-space, it is all the more important to make more space-efficient modes of transport attractive and obvious.

|

| Number of people crossing a 3.5 metre-wide space in an urban environment during a one-hour period. |

Cycling: the way ahead writes: "The mobility that we associate with the private car has merged with apocalyptic images of towns that have come to a complete standstill. A reduction in car use has become necessary if mobility in cars is to be maintained. This is also a condition for maintaining accessibility to the major centres of interest and activity in our towns. The majority of people in all European countries recognise this fact."

Now, this last sentence is telling, because for the last few years, the UK has officially been the worst place to live in Europe, with people getting a "raw deal" both on quality of life and life expectancy.

I would like to draw your attention to Professor J.E. Gordon, and his book Structures, or Why things don't fall down. I have quoted from it before (here).

Nowadays, whether we like it or not, we are stuck with one form or another of advanced technology […]. However, man does not live by safety and efficiency alone, and we have to face the fact that, visually, the world is becoming an increasingly depressing place. It is not, perhaps, so much the occurrence of what might be described as ‘active ugliness’ as the prevalence of the dull and the commonplace. Far too seldom is the heart rejoiced or does one feel any better or happier for looking at the works of modern man.

[…]

Museums, theatres and galleries, and other “such forms of ‘fine art’ can only operate occasionally in the ordinary person’s life. They may provide an escape, but they are really no substitute for an environment which is satisfying in itself and is continually present. Most of us find some sort of refreshment in the countryside, but we are pretty well resigned to the dreariness of towns and factories and filling stations and airports and most of the things with which we have to spend our day. Possibly fish which have to live permanently in dirty water may get more or less used to it—but human beings who are conditioned in this way ought to rebel.Professor Gordon asks why people react as they do to some inanimate objects. He’s talking about artifacts, actually, but his point carries across. He explains:

Within the subconscious mind there lies an enormous store of potential reactions and ‘forgotten’ memories. This material is partly inherited genetically from a remote past (Jung’s ‘collective unconscious’) and partly acquired by the individual himself during the course of his own life, mainly from apparently forgotten experiences—sometimes unpleasant ones. Now our physical senses—sight, hearing, smell and touch—continually pass to our brains far more information about our surroundings than our conscious mind can accept or be aware of. But the subconscious is monitoring this information all the time and it is full of receptors and trip-wires which are liable to be influenced by every shape and every line, every colour and every smell, every texture and every sound. We may be totally unconscious of this, but it is happening all the same and it is building up subjective emotional experiences within us—be the effects good or bad.Professor Gordon suggests that our ancestors would be horrified that we should suffer many millions of people to experience every day the beastliness of London or New York. “Therefore many of us seek some kind of relief or consolation in ‘Nature’ and we escape, when we can, to the country, because we find the countryside more agreeable than towns and roads.”

But it wasn’t always so, he says. Before the eighteenth century, when most of the landscape was much wilder, ‘Nature’ implied “not only physical discomfort, but Pan in the raw. To these people it was the towns which were habitable and attractive, the country which was inhospitable and ugly.”

“To that extent,” he says, “people—all people—in the eighteenth century lived richer lives than most of us do today. This is reflected in the prices that we pay nowadays for period houses and antiques. A society which was more creative and self-confident would not feel so strong a nostalgia for its great-grandfathers’ buildings and household goods.”

Hitting the nail on the head

In terms of what this means for developing a mass cycling culture, there needs to be a recognition that we have a long way to go. Indeed, as I see it, if we want to climb to the top of the ladder, say, then one of the first things to be done is to ensure the ladder has a secure footing.

As you'd expect, all the hard-to-deliver bits are left to the end. But look how far down the list we can get before things start to become difficult! Look at all of those positive features in the top half of the table!

I thought that a recent comment posted on the Connect London petition was very telling: "Car traffic is one of the biggest problems in most cities, and also in London. It is rarely that easy to tackle issues of public health, CO2 emissions, the quality of public space with one simple and cheap measure."

Just so. The problem is, however, that the Connect London network would not seem able to tackle these issues. Whatever else the routes are, they are not currently—and never will be, by the looks—meaningful and direct.

Routes which are not meaningful and direct are not in any way useful to regular cyclists—other than for leisure purposes, of course. If there is any evidence that such routes would be useful to more occasional cyclists, I have yet to see it.

So anyway, as I have said before, we need to make the best use of the resources which are available to us, and we need to take on board the fact that not everything can be done all in go, which means to say, we need to prioritise. Moreover, it is an important principle to obtain a proper yield for the work that we put in. I very much hope, then, that we do not allow ourselves to be persuaded that the development of a few exemplar schemes here and there would actually represent a significant step forward.

What I mean by this is that the hardest step—sayeth the eastern philosophers—is to go from zero to one. There clearly must be some truth in this, because there is not one town or city in the UK which has a functioning, comprehensive, city-wide cycle network. If it was easy to develop such a network, it is reasonable to suppose that the authorities would already have done this.

The usual way of things here has been to try to cultivate an amenable cycling environment from the bottom-up (i.e. piece by piece). And yet, despite the inescapable conclusion that this approach doesn't work very well, we appear to be stuck with it. As Ambrose Bierce suggested, habit is "the shackles of the free".

However, it ought to be possible to break free from these shackles, so to speak, and cast aside this insensible habit, simply by accepting the prudence of "introducing" the network—all of it—to a minimum level of functioning first, and then developing it further on the basis of priority interventions and a timetable. This is the tried and tested method, and all the evidence from the continent is that it works.

I very much welcome the development of exemplar routes. This is what the Mayor of London is planning with his so-called 'Crossrail' route, of course, and seems to be what Manchester, Leeds, Norwich, etc, are planning to do with the funding from their Cycle City Ambition Grant.

Clearly there a certain routes which are more useful to cyclists than others. Old Shoreham Road in Brighton is a very good case in point.

But this work done, this one route developed, then what happens? They'll do another exemplar route, will they? And then another one after that, I suppose, and keep going until eventually—oh yes, until eventually. But if this is the plan, then why not carry out this work within the framework provided by a functioning cycle network?

Pardon? Sorry, my mistake. I thought you actually said something.